Specialisms

Gender & Sexuality

What does it mean to be 'a man' or 'a woman'? More and more people seem to be asking themselves this question these days. Perhaps because our current cultural context makes it possible - or even necessary - to bring Gender issues up for re-assessment. These may be accompanied by questions about ones own sexuality (and this means a lot more than 'sexual orientation'). Gender and Sexuality relate to how we feel about ourselves as potential sexual participants in interactions with others. But they also relate to how we feel about and understand ourselves and what sexual (whatever we understand this word to mean and how we experience it in ourselves) experiences are relevant to us. We have long lived in a cultural context which tends to assume that understandings of gender and sexuality need to fit into rather fixed and limited/limiting moulds. In reality, both are extremely personal and there are possibly as many variations as there are individuals. Such standards may be constrictive and leave us feeling falling short of or different from these assumed prototypes (stereotypes) which are mostly just fictional abstractions at the end of the day. Our understanding of our Gender roles/presence and Sexual proclivities/preferences fluctuates enormously over time and in different contexts. How we feel about ourselves in our early 20s will likely be very different from how understand ourselves along the same 'lines' in mid-life or later-life for example. How we behave in embodying genders and sexual codes/rites in 'meeting to mate' environments is likely to be very different from how we feel in less 'sexualised' environments. Different countries/cultures may bring out different ways of relating to our gender and sexual identities, whether by choice or because of social pressure. What feels sexually interesting or attractive one summer may be very different from the next winter, and different people whom we engage with and relate to at a more intimate level may bring out different aspects of our femininity/masculinity or of our sexual fantasies, desires, mysteries and subtleties. It is important to find ways of familiarising ourselves with these most intimate and personal aspects of our existence so as best to gain control over what parameters we choose to apply when making decisions about how to engage with the world (others) along gender and sexuality lines. Freud famously highlighted the primacy of the Sexual Instinct in everyone's life. At a very basic level, we are biologically primed to follow instinctual forces which might ultimately lead to 'mating'. But the reality of our experiences goes much further than than these animalistic impulses. Later in life and in the body of his work, Freud highlighted the affinities between the Sexual Instinct (and the Libido) and the Life Instinct - a force to be understood in a much broader sense, one that operates in much more sophisticated ways throughout life. It drives our interest (in all degrees of intensity) in just about anything, from food to philosophy, from dance to politics, from going for a walk to building our lives according to our own individual vision. Not many people know this, but Freud's idea of what constitutes an instinct includes a lot more than its object. As far as Freud is concerned the gender of the person one may be attracted to (object choice) is only one of the elements at play. He considers the source (need) and aim (satisfaction) equally if not more important (he says the object is largely incidental in comparison to the other elements), but also the 'quantity of energy' (investment) pressing those pedals at any one time as crucial to understanding our (varying) experiences of the instinct within ourselves. Many other psychoanalysts have taken this much further (and the issue of object-choice appears as rather secondary if we consider the significance of everything else that plays into what we consider as 'sexuality'). From the angle of the 'Oedipus Complex' or of Attachment, from the different types of relationship (love, excitement, friendship, loyalty, dependence, cooperation, etc) we experience throughout life, from issues of 'projections' and the 'repetition compulsion' we sometimes unconsciously establish in patterns of behaviour or choice to aspects of our sexuality we repress (unconsciously driving that energy to come out in very disguised - and often pathological or 'neurotic' - ways) or consciously choose to suppress and 'sublimate' ('channelling' it into other pursuits), the field of gender and sexuality opens a huge territory which each individual needs to map for themselves as they deploy their individuality in the way they choose to relate to the external world of relationships out there. Many people suffer from getting caught up in a narrow perspective (often exploited in the language of 'popular psychology' espoused in glossy magazines or self-help books or soup-operas or rom-coms) which assumes that there are fixed 'recipes' for successful sexual relationships. This 'matrix' may often be more of a hindrance than a help. In experience, gender and sexuality are a journey - often experienced in the context of relationships - which even when the plotline follows the 'boy meets girl' prototype, is in actual fact subject to all sorts of variations, u-turns, surprises (welcome or otherwise) and learning curves. Navigating these may benefit a lot from careful attention to all the levels at which we relate to ourselves as well as to others. Our feelings are inevitably triggered (if they are not then that in itself may need attention) and processing them may help us move on with a sense of being able to have more choices after having learnt from the experiences. French Psychoanalysts (not only Lacan or the psychosomatic school) have paid a lot more attention to how we relate to experience life through our bodies (Freud did say that the Ego is primarily a bodily one) and their influence keeps reminding us that we separating ourselves from our incarnated experience may come at a high price.

Learn More

Creativity

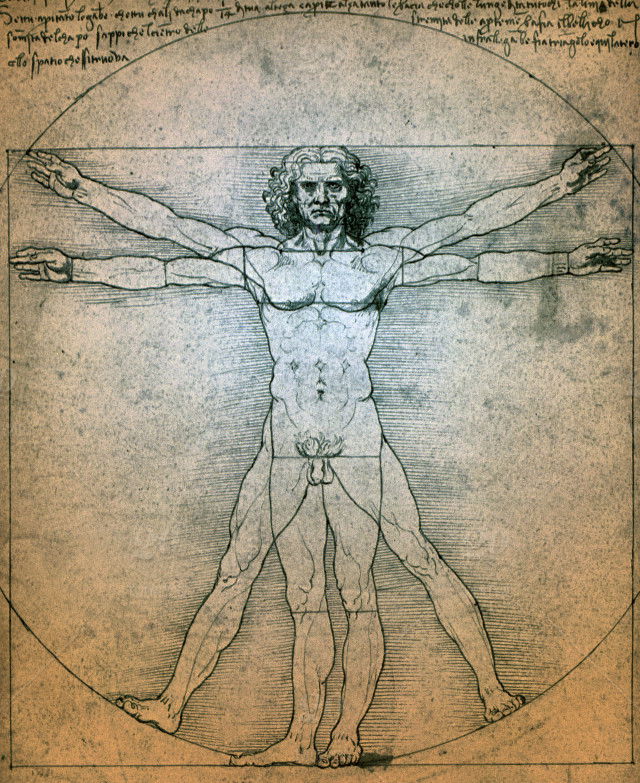

How we impact on the world around us. Crieativity is a lot more than being able to draw/paint/sing/dance/write or invent whatever. As human beings we are constantly altering the physical environment around us in myriad ways, from the minute we make breakfast or write an appointment into our diaries we are altering reality through some sort of 'muscular' interaction with it. Sometimes this is not consciously intended - our mere live presence brings with it the temperature of our bodies, the CO2 we breath out, the noises we make as we move around. We often take all of this for granted, but if we think of it carefully, these are all ways of having an impact on the external world. At a very basic level our most primitive primate ancestors would have done the same by picking up a fruit from at tree or expelling the toxins from their bodies back into the ecosystems which transform them into manure to feed the complex cycles of nature. As we developed as human beings we developed more sophisticated ways of affecting our environments, from the basics of 'science' (making pots and pans, using fire to cook, making arrows to hunt, curing furs to protect from the cold, etc.) we went further and created language and art (at their most basic) - this is what anthropologists call 'civilisation'. What we understand as civilisation today is however a much more complex set of ways of operating than that. The psychological (in the broader sense) aspects of it are what tends to occupy our conscious minds most of the time these days. This leads to what we commonly call 'thinking' - we try and 'work out' what needs to be said or done in any given situation so as to use language (operating at many levels) to obtain the aimed results (that same fruit our primate ancestors would have picked up from the tree). The capacity to symbolise (the use of languages - and these are not just verbal/written) marks the development of our psyches as well as that of civilisation. Through languages (words, as well as gestures, expressions, visual signals or productions, etc - all building blocks of what is commonly alluded to as the 'arts') we are constantly affecting the (social) world around us -and not just to obtain the concrete results consciously aimed at, but to enrich our own internal capacity to 'think' (in ways which far exceede pragmatic concerns) to feel and experience, and to bring these out into the (social) world - what is commonly understood as 'expressing ourselves. How we are constantly developing our own individual ways of doing this is what Creativity ultimately is. Whether we are talking about Da Vinci's Mona Lisa or Bethoven's 5th, the palace of Versailles or Shakespeare, or whether we are considering how you chose to comb your hair today or how the tome of your voice of the twinkle in your eye as you asked for your coffee this morning, how you wish your office chair had more comfortable padding or what words you chose for your e-mail just now, we are talking about your own individual creative potential. Tapping into this vein empowers us with many choices. Many people suffer from feeling insignificant and impotent in the face of having to respond to an increasingly codified word in 'standard' ways. The internet is awash with such recipes... and they come not only with 'helpful tips' and templates, but also with pressures to conform... This pressure to conform can be experienced as reassuring (if we feel we know what is expected of us) but may also contrive to enslave us to a robotic existence which robs us of our creative leeway... No wonder feel they need to find 'outlets' for their 'creativity' and will look for (yet again) standardised and codified ways of doing so (by taking art lessons, learning to play an instrument, buying a fashion magazine). These often create the illusion of freedom that we hanker after but ultimately co-opt our creative impulses into regurgitating models devoid of spirit. Creativity is ultimately unforeseeable and learning to live with this force inside us is an endless source of life energies not to be underestimated. Creativity risks changing - not just the colour of your curtains or the sound of your voice or the shape of buildings we live in or the number of books the next best-seller sells - but the way people perceive, think and live their experiences for some time (sometimes for quite some time!). And this makes it a 'dangerous' force (which is the reason why it is often institutionally and culturally thwarted...) Finding - and making the most of - these precious sources within ourselves empowers us to live a fuller life. Failing to do so may lead to a build up in levels of conscious and unsconscious frustrations leading to many states of mental/psychological suffering, from an abiding sense of powerlessness and futility to dangerous levels of resentment and rebellious destructiveness (often turned against ourselves). Creativity also means really engaging not only with the constructive side of 'bringing sth into existence' but also with the inevitable destructive side of any such decisions we make in life. To paint a picture we deed to attack and destroy the blank canvas, to create music we need to be bold enough to break the silence, to write a story or say sth we make daring decisions about all the stories we shall not write, to build a house we destroy nature as it was on that spot, possibly for ever! Every act of creation (even a post on Facebook) entails some destruction and coming to terms with our destructive potential is sth psychotherapy does not take for granted. If we are not familiar with our own destructive potential we often end up acting it out in unconscious ways - either against others or against ourselves. Creativity helps us atone for such destructive impulses by making it worth while in what we choose to create. Life is a constant recycling of such forces: As we eat our bodies destroy the prime materials of nourishment and expertly (hopefully) choose which elements to metabolise into life and which to discard and get rid of. As we breathe we do the same. Other elements in nature will use our destroyed ejects to create (metabolise) life for themselves. In life we are always ultimately walking in the direction of self-destruction (natural death) and self-wastage (old age), but in the process of doing so we create the seeds of life that outlives us - whether our children, the houses we build, books we write, etc. but most importantly how we affect others in and through our lives - and these shall 'ripple' in ways we often cannot control.

Learn More

Transitions

Time and Tide wait for no Man. Change is the only constant. We are always changing and so is life and everything around us. That is the nature of all living things, and even the so-called inanimate world is always passive to being changed somehow. Change may be cyclical, day to night, summer to winter, cold to hot, dark to light, big to small (and vice versa in all directions as in the Yin/Yang symbol the seeds of movement into ones opposite are always there in and in operation). But evolution is also change. As babies we change very fast - there's a lot to learn and much growing to do! But in the face of so much change (which babies often relish in as they know the direction of their lives is evolution) we need to deal with much anxiety: How are these changes coming about? who is helping? Are they reliable? Does their help match my needs? In good enough contexts, the final balance of how we experience the 'answers' to these 'questions' (felt, not articulated) is 'good enough'. We find what we need is sufficient quantities, of a good enough quality, and sufficiently frequently. We gain confidence in both the environment's capacity to provide and in our own capacity to make good use of what it provides. And we may thrive or fare well in our relationship with changes (external and internal). This balance is however, not matter how well achieved, always to some extent precarious (as is our life - as any picture of the planet seriously considered quickly demonstrates.). Our vulnerability in the face of much bigger and powerful elements (the sea, mountains, outer-space, a vulcano, etc.) is paradoxically the source of what has been conceptualised as the 'sublime' but also the 'uncanny'. Undersdanding our insignificance and our mortality (and the passage of time and of everything else) is often what paradoxically gives meaning to the ephemeral nature of life. Despite such grand aspirations, the survival instinct is always on the alert for 'the next meal'. It needs reassurances: shall I have what I need tomorrow? It craves constant provision (what Klein called 'the perfect breast' - always available, and providing all I need, just when I need it, and just the way I need it!). Any changes to such reliability is a challenge that may bring up big anxieties (and sometimes they do feel like life-or-death!...). Much as the toddler wants to develop their ability to walk and run and go places, it likes to know that mum is within reach and so looks back to check (reassurance). What we commonly call 'confidence' largely depends on this: as we develop our ability to deal with the challenges of the world and day-to-day life, we like to know what we can fall back on, what we assume we can always count on 'just in case'. This can be our families, our home, the particular strengths that have served us well, a 'comfort blanket', a faith, social structures (like the Swiss trains, the salt in the sea, 'bricks and mortar', or pay cheque at the end of the month). Stable societies and cultures, above and beyond any reservations or critique, often provide this 'bedrock' of social, economical, philosophical foundations which allow people to feel secure enough, regardless of what happens to them. When changes break these assumptions we experience them as traumatic.... Trauma shakes up our whole World View. Suddenly we no longer know what is reliable and what is not, because what we previously considered 'impossible' has just happened... The human psyche finds it very difficult to cope with this. It may 'choose' to 'withdraw' from reality (and even deny its existence) or to concoct other ways (called defences) to compensate for or concoct a sense of safety in some other way (often fictitious), in a desperate attempt to recover the lost sense of trust and reliability on what we had assumed would never let us down. Disappointments always hurt, sometimes more than others. And the scale comprises feeling disheartened or even disillusioned, or completely betrayed (and rather shattered in what we had previously believed to be the truth of reality or of ourselves). Despite the fact that we may know that change is always there and inevitable, we find it much more difficult to deal with change which we do not expect, understand, want, which we had not sought, have no choice over or power to control, and which have a knock-on effect on other areas of our lives which we had not anticipated... The 'back to the drawing board' position is often unpleasant (and it may take us some time to realise that we even have a drawing board to go back to!...). Loss is a constant in life. And the concrete objects we are often sorry to lose only stand for changes which entail much more meaningful changes: the loss of childhood, of innocence, of loved ones, of status, power, position, popularity, abilities, capacities, and ultimately that of our own lives. All cultures develop ways of ritualising the passing of significant losses and of honouring the objects of our experiences of loss. This shows our instinctual appreciation for the significance and profound impact (and risks involved) in such transitions. Our emotional/psychological well-being is invariably affected - even if temporarily - by such experiences and for our own sake it is important to find ways to process ('mourn') our losses. Freud's paper 'Mourning and Melancholia' is the seminal psychoanalytic text in this respect - and the ultimate acknowledgement of the risk of Deppressive states of mind when the processes of facing loss go askew... In our psyches (and in our hearts) we do not lose 'suddenly' - it is a gradual process - and never completely 'accepted as a matter of fact' - it depends on a series of internal transformations. Like when a tree in the middle of a forest falls, all the other trees need to adjust gradually to the clearing that is left, and what results is often a landscape of negotiated alterations, rather than a like-for-like replacement, or a simple 'leaving the lack as it is'. These adjustments are what we mean by the psychological experience of transition - not a simple - or linear - task. But, as the clearing in the forest also offers new possibilities, so do the meaningful losses in our lives. Ultimately the person we become is a collection of all the losses we have had and how we have dealt with them. Here again, there is no recipe. Each individual creates their own internal landscapes as they go along. Like the veins in the trunk of each tree are never the same, each developed organically according to innate tendencies as well as circumstantial conditions. Psychotherapy aims to honour this process and facilitate its organic unfolding while making space for the internal richness that comes with pain.

Learn More